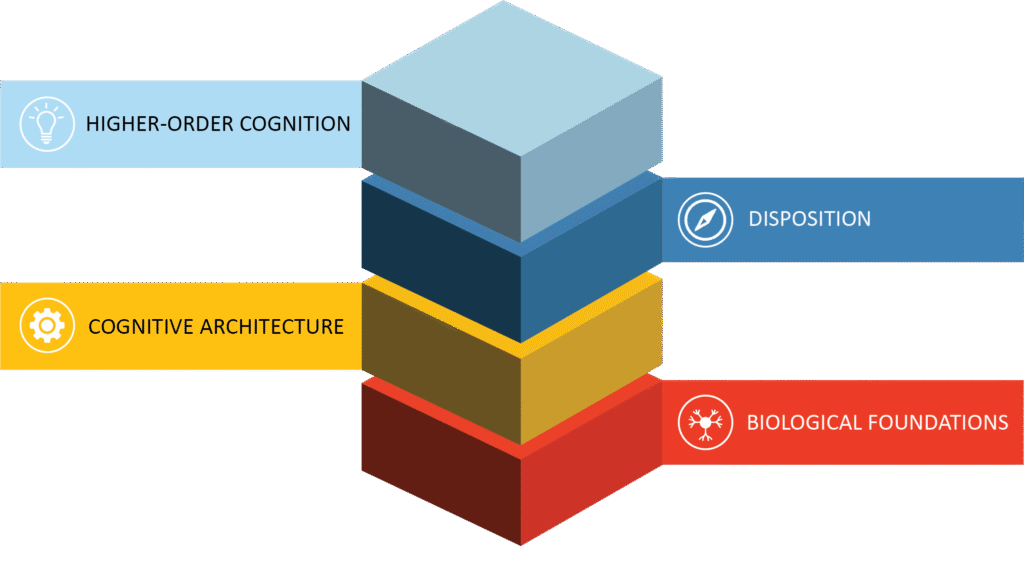

The Layered Neurodevelopmental Model (LNM)

The Layered Neurodevelopmental Model (LNM) offers a framework for understanding psychological functioning not as a collection of isolated traits, test scores, or diagnostic labels, but as the outcome of dynamic interactions across multiple interdependent systems. It is grounded in a central proposition: the human mind is a structured and developmental phenomenon shaped by layers of biological, cognitive, motivational, and regulatory mechanisms.

Rather than focusing on deficiencies or deviations from statistical norms, the LNM centers on structural configuration—how an individual’s system is built, how it has developed over time, and what forms of support align with that architecture. This perspective facilitates a more precise understanding of variation and adaptation, particularly in contexts where conventional models fall short.

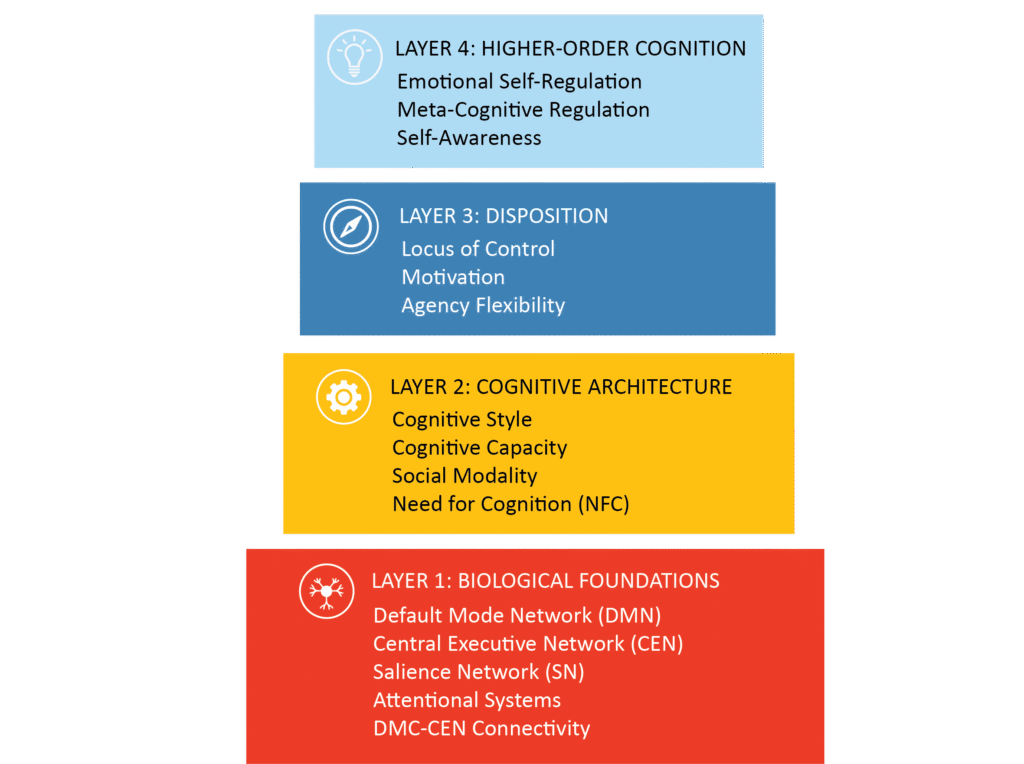

The model defines four primary layers, each of which contributes to the organization of the mind. These layers are not discrete compartments but interacting systems that co-develop across time, influencing both internal experience and external behavior.

Layer 1: Biological Infrastructure

The neural foundation of psychological functioning

The first layer—Biological Infrastructure—comprises the foundational neural systems that regulate the baseline dynamics of perception, emotion, attention, and internal stability. Rather than describing the biological components individually (e.g., brain regions or neurotransmitters), this layer focuses on network-level systems that coordinate cross-domain functioning and establish the initial parameters within which cognitive, motivational, and regulatory capacities develop.

Core systems include:

- Default Mode Network (DMN): Supports self-referential thought, narrative construction, and autobiographical memory.

- Central Executive Network (CEN): Governs working memory, goal-directed planning, and attentional control.

- Salience Network (SN): Monitors internal and external stimuli, orchestrating shifts between introspective and task-focused states.

- Attentional Systems: Regulate prioritization and shifting of focus across multiple stimuli and internal states.

- Network Coupling (e.g., DMN–CEN): Manages transitions between reflective and action-oriented modes of processing.

These networks form a dynamic infrastructure that interacts with, but is not reducible to, localized regions, neurotransmitter concentrations, or hormonal cycles. While such biological substrates (e.g., dopamine, amygdala, cortisol) contribute to the operation of these systems, they are not equivalent to the functional layer itself.

Why it matters:

This layer defines the initial boundary conditions for development—sensory thresholds, emotional rhythms, and attentional biases that constrain and shape the emergence of higher-order processes. Although relatively stable, especially after early development, the biological infrastructure interacts continuously with cognitive and regulatory systems, forming the base upon which individuality is built.

Layer 2: Cognitive Architecture

The structure of thought, interpretation, and information processing

Cognitive architecture refers to the organizing principles through which individuals process information, construct meaning, and engage with internal and external complexity. It includes preferred cognitive styles, conceptual capacity, social orientation, and the drive for mental engagement.

Core dimensions:

- Cognitive Style: Preference for narrative (experiential, meaning-based) vs. logical (abstract, rule-based) processing.

- Cognitive Capacity: Dominance of semiotic (symbolic, intuitive) vs. logical (structured, categorical) reasoning modes.

- Social Modality: Cooperative (scaffolded by social interaction) vs. individualistic (self-guided, internally coherent) interpretive strategies.

- Need for Cognition (NFC): Degree of intrinsic motivation for effortful thinking, ranging from low (preference for simplicity) to high (preference for complexity and novelty).

Why it matters:

This layer determines how individuals encode, represent, and respond to the world. It mediates learning, social communication, and cognitive flexibility. The configuration of this layer influences both educational engagement and problem-solving patterns, and interacts dynamically with motivational and regulatory processes.

Layer 3: Disposition

The motivational and agentic structure of the individual

Dispositional patterns shape the direction, intensity, and flexibility of behavior over time. This layer reflects internalized frameworks for action, initiative, persistence, and adaptation, emerging from cumulative interactions between foundational biology, cognitive preferences, and environmental reinforcement.

Core dimensions:

- Locus of Control: The perceived origin of outcomes—internal (self-directed) vs. external (externally imposed or chance-based).

- Type of Motivation: Intrinsic (curiosity-, purpose-, and autonomy-driven) vs. extrinsic (compliance-, reward-, or avoidance-driven).

- Agency Flexibility: The capacity to adjust behavior, revise strategies, and recover from setbacks—ranging from flexible to rigid patterns of engagement.

Why it matters:

Dispositional structure determines how individuals mobilize cognitive and emotional resources in the face of challenge. It shapes not only action tendencies but also long-term resilience, self-direction, and developmental trajectories. Inflexible patterns often emerge in response to punitive or chaotic environments, whereas flexible agency is cultivated through autonomy-supportive experiences.

Layer 4: Higher-Order Cognition

The reflective and self-modulatory capacities of the system

This layer encompasses meta-cognitive and emotional regulation abilities that allow individuals to monitor and adjust their internal processes. It includes the capacity to observe one’s own thoughts, regulate affective states, and align behavior with long-term goals and self-defined values.

Core dimensions:

- Emotional Self-Regulation: Ability to recognize, modulate, and recover from affective states in accordance with situational demands.

- Meta-Cognitive Regulation: Capacity to reflect on, evaluate, and adjust cognitive strategies, including planning, monitoring, and revision.

- Self-Awareness: Insight into one’s own beliefs, motivations, and behavioral patterns, enabling reflective identity development and intentional transformation.

Why it matters:

Higher-order regulation allows for adaptive flexibility, especially under conditions of novelty, ambiguity, or stress. It serves as a modulatory layer, influencing lower-level dynamics and enabling conscious reconfiguration of behavior over time. The development of this layer is critical for autonomy, coherence, and psychological maturity.

Dynamic Interdependence Across Layers

These four layers do not operate in isolation. Their interactions shape the structure and function of the individual mind across time. For example, a strong sense of intrinsic purpose (Layer 3) may help mitigate biological anxiety (Layer 1), while underdeveloped emotional regulation (Layer 4) may inhibit the effective use of analytical reasoning (Layer 2). The interdependence of layers allows for compensatory mechanisms, developmental shifts, and personalized pathways of adaptation.

Rather than pathologizing deviation from statistical norms, the LNM conceptualizes difference as structural variation—emergent from the interaction of developmental systems. This reframing enables a more nuanced understanding of both challenge and potential, particularly in neurodivergent configurations.

Implications for Human-Centered Design

Understanding the mind as a layered and dynamic system has broad implications for how support systems are conceived and implemented. The LNM provides a foundation for designing environments—educational, clinical, occupational—that are structurally aligned with individual configurations rather than governed by abstract norms.

This approach enables:

- Support strategies tailored to developmental architecture rather than surface behavior.

- Reduced reliance on deficit-based diagnostics in favor of structural insight.

- The creation of systems—schools, therapies, workplaces—that accommodate rather than constrain human variation.

In contrast to one-size-fits-all models, the LNM offers a framework that is both integrative and respectful of complexity. It advances a more precise, ethical, and human-centered approach to understanding the architecture of the mind.